The Finnish Offensive Phase

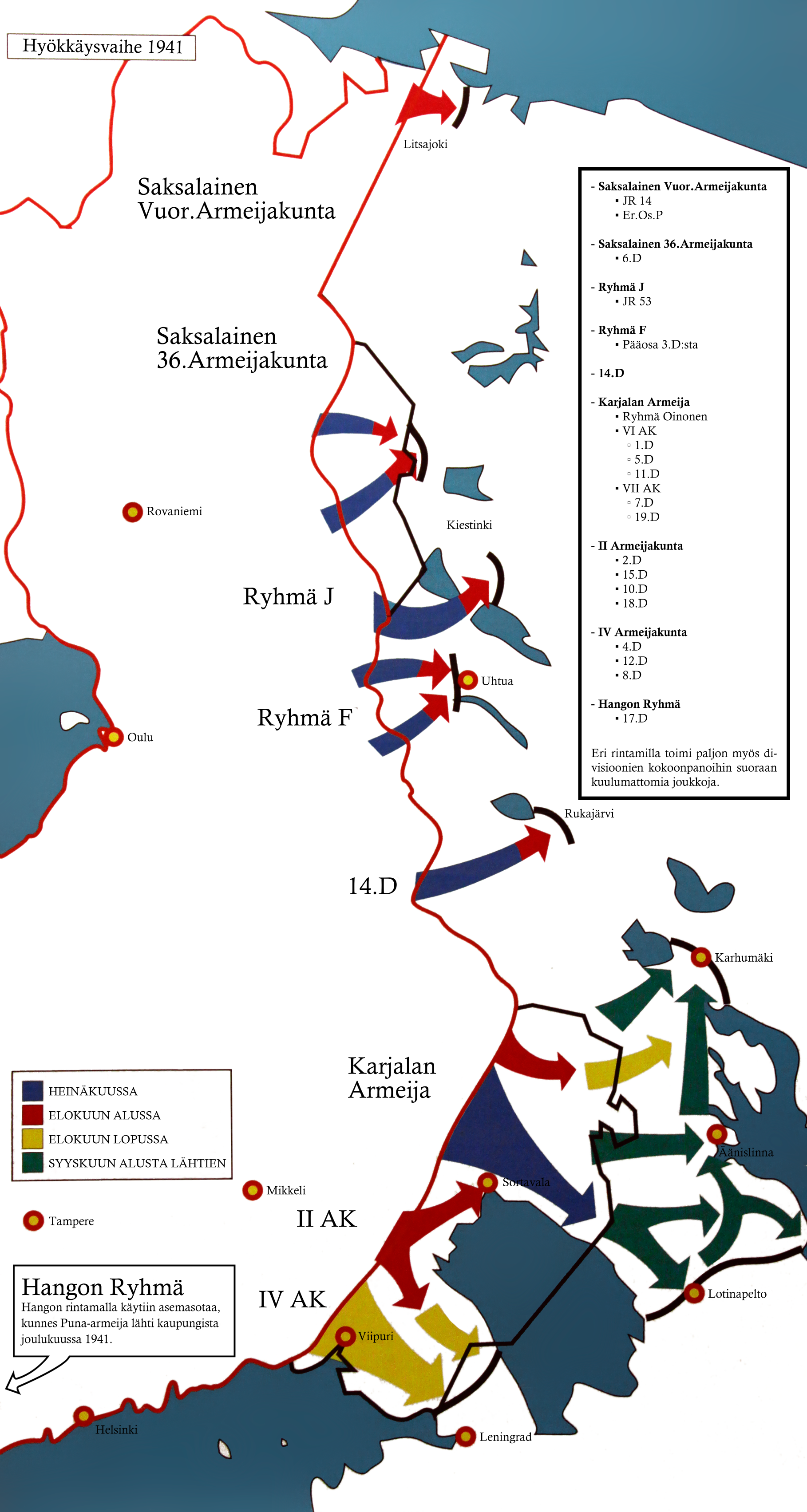

As Germany's attack on the Soviet Union approached, Finland ordered a general mobilization on June 17, 1941. The 16-division field army was stronger and better equipped than during the Winter War. In addition, strong German forces were present in Northern Finland. After mobilization, Finnish troops positioned themselves in defensive formations near the border. Germany launched its attack on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. Although Hitler declared in his speech that Finland was fighting alongside Germany, and German forces also used Finnish airspace for their offensive, Finland formally sought to maintain its neutrality. The Prime Minister declared that Finland was at war only after the Soviet Union bombed Finnish cities on June 25. In early July, the main Finnish forces crossed the border first north of Lake Ladoga, and eventually in August on the western Karelian Isthmus.

The Finnish offensive progressed rapidly. North of Lake Ladoga, the old border was reached on July 22. The advance continued into East Karelia. The attack was halted at the River Svir and partially beyond it. Further north, the advance reached the Maaselkä Isthmus and the area of Rukajärvi. In the German sector, only limited gains were made beyond the Finnish border. On the Karelian Isthmus, the advance was stopped slightly south of the old border. Despite German pressure, the Finnish forces did not continue their offensive toward Leningrad, which nevertheless was encircled from the south by German troops. On the Hanko front, the situation mostly remained in stalemate. In early December, the Red Army withdrew its forces, and the Finns entered the now-abandoned town. By December 1941, Finnish objectives on the front had been achieved, and the army transitioned to a defensive posture.

Finland’s primary goal had been to reclaim the areas lost in the Winter War. The advance deep beyond the old border caused some opposition, both among field troops and on the home front. There were also instances of soldiers refusing to fight, influenced in part by the exhausting nature of the offensive warfare. Politically, Finland found itself in a difficult position due to the territorial conquests. Marshal Mannerheim’s order of the day in early July had drawn attention, as he referred to the 1918 promise to liberate East Karelia. However, the continued advance could also be justified on military grounds: waterway lines and isthmuses were easier to defend than a continuous land front. Despite strong German pressure, Finland refused to cut the Murmansk railway or attack Leningrad.